(Photos are below.)

Ed has taken us all through our Scottish music & to the Highlands tour to give you a flavour of Scotland, its music and landscapes.

In Ed's recent post about Stirling, we finished at the site of the Borestone, where Robert, King of Scots raised his standard against the English Edward II at the Battle of Bannockburn.

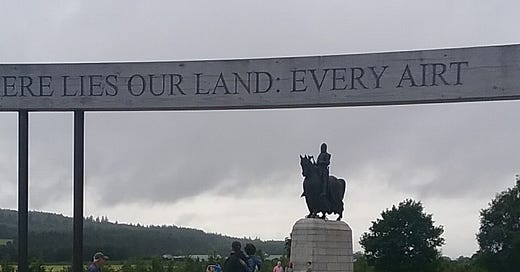

I live not far from there, and when walking through, always stop and read the poem of Scotland's Makar, Kathleen Jamie, which is engraved on the surround of the Borestone Rotunda.

“Makar” is the national poet or bard. In our past, till the 17th century, Scotland's poets, bards and musicians were much revered and supported by all, people and the royal court. Think of Niel Gow and the support for him from the Duke of Atholl. All forms of culture were, and are, prized and supported. Our trips try to explore and hear some of the Makars of the past and their works. Well, Kathleen is our current Makar.

Her poem was commissioned for the 700th anniversary of Bannockburn, and was carved on the rotunda of the Bruce statue on the battlefield. Kathleen Jamie captures the essence of the Scots through the ages.

Here lies our land: every airt Beneath swift clouds, glad glints of sun, Belonging to none but itself. We are mere transients, who sing Its westlin’ winds and fernie braes, Northern lights and siller tides, Small folk playing our part. Come all ye, the country says, You win me, who take me most to heart.

Below are Kathleen Jamie’s comments about composing this poem:

“From the start I wanted this piece of work to make a nod to the Scottish literary tradition. More than a nod – a profound bow. Because Barbour, Burns and Scott had all written about Bannockburn, and had all done so with a 4-beat line, I decided my piece would be in tetrameter too, as a homage.

“That was the form.

“As to the tone, it didn’t want to be didactic and certainly didn’t want to be triumphalist. I sought a tone which suggested shared experience and quietude -especially because people who had been through the visitor centre before approaching the rotunda would have been subjected to a lot of medieval battle-clamour; their minds would surely be loud with nationhood and self-determination. For them, as for the local people who walk there, the rotunda would be a place of relative peace, contemplation, space and fresh air. I wanted to make the inscription reflect that, and to say something generous.

“Visiting the rotunda and the statue, I noticed the way the land seems to wheel around that site. Bruce knew that too. I wanted to write about the land, and our attachment to it. Just being up at the rotunda gave me the simple first line: Around us lies our land. It was a blustery September morning, so the next line came easily too: Beneath swift clouds, glad glints of sun.

“So far so unarguable. But I knew I wanted to say something else. That the Scots may have ‘won’ Bannockburn, but not the land itself. We may exploit the land but everything changes and we pass away and the land endures. Hence the next line: Belonging to none but itself. Already my tetrameter was slipping! Only three beats in that line but fair enough. A bit of ballad metre, what could be more traditional?

“All this thinking about land and tradition led me to consider the centuries of Scots song, much of it about landscape. Because the rotunda frames two cardinal points (or airts) I thought it would be neat to refer to all four of them. But why do it myself when my forebears had done it so much better? Burns was on my mind so I wrote down ‘westlin winds’.

“Then I looked south. What could represent the South? Soon I thought of ‘the fernie brae’, that magic road which took Thomas the Rhymer from under the Eildon Hills into fairyland. So far so good. What for the east? East of Bannockburn winds the Forth, which is tidal as is the Bannock Burn itself, a fact Bruce exploited. Eastward was the river and tides and the North sea, so the phrase ‘siller tides’ came to me, from Violet Jacob’s haunting poem, ‘The Wild Geese’. Now only north remained and there I was stumped for a while, not least because I wanted to include something urban, a town or city, as befits modern Scotland. I was at home by then, and mulled it over for a day or two before being struck by the obvious: the ‘northern lights’ (of Old Aberdeen, of course!).

“So the four cardinal points were in place, simply by quoting from a heritage of Scottish poetry and song. The presence of these poets pleased me greatly.

“The last line was ready by then, too. If the land could speak, I’d wondered, what would it say? Something welcoming, hopefully. Something that opened out our vision and sense of ourselves. Something about belonging not to those who ‘own’ it, but to those who love it. So the very last line was fashioned. And then there suddenly arrived the phrase Come All Ye, surely the most open-handed gesture in all Scots literature. It fitted nicely in the penultimate line and I was thrilled to have Hamish Henderson join the list of poets represented.

“It was almost done, but something was missing. Line 7 was still a blank. Knowing a full rhyme on ‘heart’ would give a fine sense of closure, I mumbled through the alphabet till I got to P, and Part. Toying with the word ‘part’ gave ‘playing a part’. Who plays a part, in this land? Well, we do. Everyone does. And in that instant ‘small folk’ dropped into place. The ‘small folk’, of course, being the ordinary Scots who turned out at Bannockburn, and sent Edward homeward to think again.”